by Dr. Andrea Paz

Once, during my graduate studies in New York, I was talking to a classroom of 3rd graders about being a biologist from Colombia, when I was interrupted by one of the kids. “I am from Ecuador, and I recognize those landscapes!” he said. I had a similar experience while Zooming with a class of 5th graders in Illinois. The majority were Latino students, and they were fascinated to meet a Latina scientist – and curious to know if they could pursue such a career, too. “Do you know another Hispanic scientist?” they asked. ”Do you know other women scientists?”

Representation matters

I understand why the students reacted this way. Since leaving Colombia in 2015, I have discovered how important it is to have mentors and role models who look like me. This seemingly small thing makes me feel like I, a Latin American woman, belong in science.

I want to help kids feel like they belong, too. During my PhD, a program called Global Classrooms let me talk to K-12 classes in New York City about my home country, sustainability, and science careers. It was always deeply rewarding to see how my presence in their classrooms helped students feel represented.

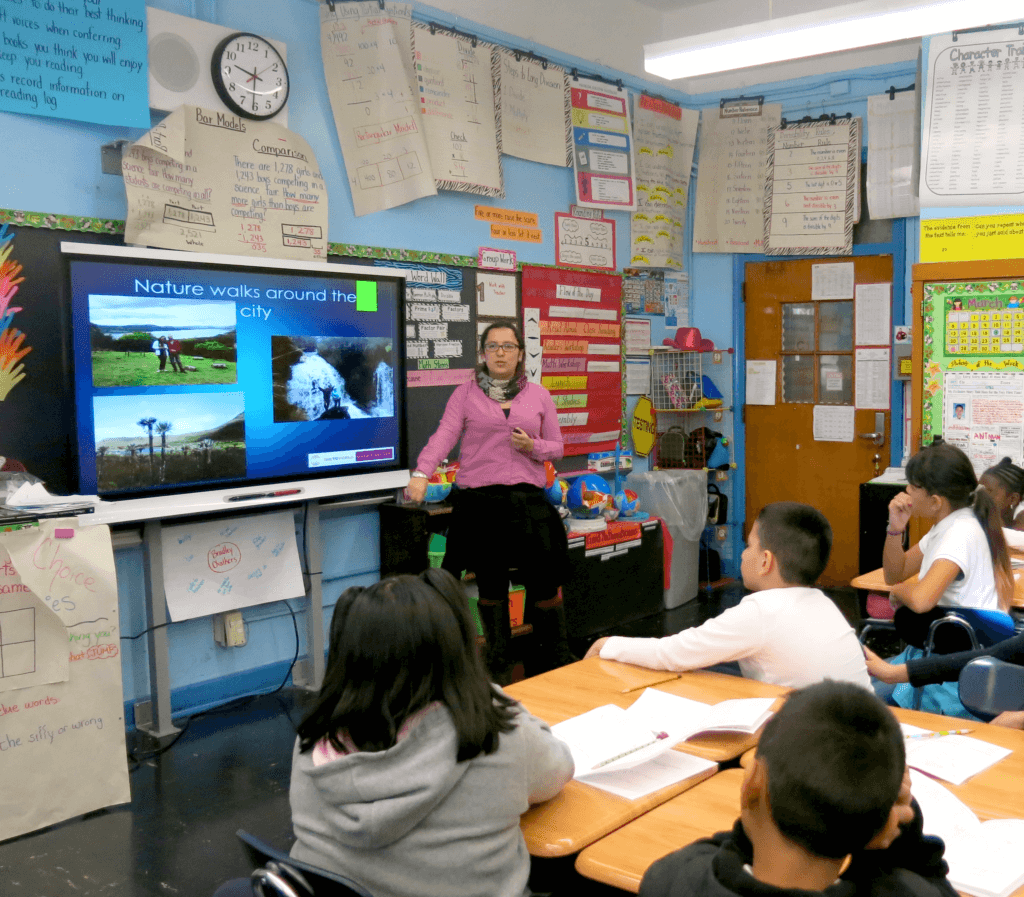

Visiting a classroom in Queens, NY to talk about sustainability, water, and energy.

Women in science

I went on to join an initiative called 1000 Girls 1000 Futures, which pairs 13 to 17 year-old girls who are interested in STEM with female scientists all over the globe. This program is virtual, allowing girls to meet with different mentors throughout the school year to discuss college, science, and the experiences of women in science.

I learned so much about girls’ lives in different cultures, and I loved sharing my own path in science with them. The program helped me recognize that because I didn’t have many role models in science as a teenager, I nearly didn’t pursue a career in science.

Even in college, almost all my science professors were men, and all the labs in my field were led by male professors. In graduate school, I finally got to meet other women pursuing science careers, and later I was surrounded by an amazing array of women professors who were hired at my university while I was completing my master’s degree. These women showed me the struggles and the possibilities women encounter in science, and I have to thank all of them for showing me the way.

With 1000 Girls 1000 Futures, my goal was to pass on that encouragement, even as I continued to see firsthand how many challenges girls still face trying to enter the STEM world.

Skype a Scientist: outreach during COVID

When the COVID pandemic hit, I joined another virtual program. Skype a Scientist matches scientists with K-12 classrooms according to their interest, language, and time zone.

After connecting with a teacher, I prepare a presentation on the topic of choice and the students send me some questions in advance. The virtual classroom visit lasts at least an hour; I present for maybe 15 to 20 minutes and then spend the rest of the time answering lots of questions from the students. (I get a lot of questions about my frog research, like “What is the difference between frogs and toads?” and “Are all frogs poisonous?”)

A virtual visit with a class in Mexico in 2022 to talk about frogs.

So far, I have done these remote visits in English, a mix of English and Spanish, and Spanish. Most schools I’ve been paired with are in the United States, so I was especially thrilled to present to a school in Mexico earlier this year. I love contributing to schools in Latin America so children can see people like them in a science career. Although each classroom visit is a bit different, I have found students everywhere to be extremely engaged in the conversation, and my visits can spark wonderful conversations about women and Latinxs in science.

How interacting with children makes me a better scientist

Getting out of the academic bubble and into the public sphere has benefited me, too.

Visiting K-12 classrooms in person and virtually mentoring high schoolers has made me a better communicator: kids call me out anytime I use jargon, and I’m learning to tell stories, not just share facts. Most importantly, these experiences have affirmed how much it matters for kids to see themselves represented in STEM. Each time I talk to a classroom, I hope I can plant the idea that science is a path they can pursue, too.