Oryctolagus cuniculus – otherwise known as the European rabbit – is an adorable little creature. Native to Southern Europe and specific regions in North Africa, these rabbits have made their home in the short grasslands of Portugal, Spain and Western France – as well as in the Atlas Mountains. Yet, it’s often considered invasive in certain regions. Why is that? Due to their ability to avoid predation, reproduce rapidly, impact population dynamics and potentially destabilize food webs. Basically – too much cuteness can really impact ecosystems and harm native biodiversity around the world from Argentina to Australia.

Biodiversity matters when it comes to invasion

In their native ecosystems, where rabbits have evolved and co-existed alongside the rest of the food web, they are an essential component of the ecosystem. The animals form a critical part of the food web as a keystone species, as prey to Iberian Lynx and Spanish imperial eagle among other critical species. They play a critical role in keeping vegetation in check after wildfires. They’re critically important for ecosystem functioning, and they are endangered in their native habitats across the Iberian Peninsula.

However, outside of their native ecosystems, rabbits are not always in balance with the surrounding ecosystems. And they can damage biodiversity by consuming young plants, reducing plant diversity, and altering the structure of plant communities. Their burrowing behaviour can also lead to soil erosion and destabilise native habitats. But they are also hugely damaging to agricultural systems, where they can completely transform the productivity of entire landscapes. In Australia alone, the agricultural and horticultural damage caused by rabbits causes $206 million AUD in damage per year.

But, to protect against these threats, nature is so often our greatest ally. Specifically, one of the best protections against these damaging effects is biodiversity itself. In areas where biodiversity is robust – where there is also a lot of biotic resistance – there are lots of competing species and predators that can control the rabbit populations. In general where biodiversity is high, the damaging effects of invasive rabbits tend to be relatively small. This is the case of Chile, where ecologists hypothesise that the rabbits have been buffered by native predators, competition by native prey and where a variety of plant species ensures that some species will always survive.

Because it turns out that biodiversity buffers against invasive species.

The same holds true for trees.

High native biodiversity buffers against invasion severity

New research from Crowther Lab at ETH Zurich reveals the importance of human activity in increasing invasions of non-native tree species, and shows that high native diversity, particularly functional and phylogenetic diversity, is key to minimising invasion severity.

Much like rabbits, invasions of non-native trees can have considerable ecological and economic impacts. A new global analysis highlights which regions of the world are most likely to be affected by non-native tree invasions. Proximity to hubs of human activity like ports significantly influences the invasion risk of non-native tree species, but high levels of native functional and phylogenetic diversity can minimise the extent of invasion.

Human activity has, both intentionally and unintentionally, driven the spread of plant species to areas far outside their native habitat. About 10% of all non-native plant species become invasive, often resulting in considerable ecological and economic impacts in the invaded ecosystems. A new study in Nature can now support ecosystem management efforts by highlighting the regions that are most susceptible to the presence and spread of non-native tree species, and identifying management strategies to minimise invasion success.

The study is the first to combine human and environmental factors to analyse non-native tree invasions at the global scale and in doing so sheds light on the invasion strategies of non-native plants. In locations that experience extreme cold or dry conditions, non-native species need to be functionally similar to the native species to survive in these harsh environments. In contrast, in locations with moderate temperatures, non-native plants are often dissimilar to native species as they must differentiate themselves to avoid intense competition.

However, the study reveals that proximity to human activity – particularly to ports – can override these ecological factors in predicting invasion. Yet, native biodiversity, specifically evolutionary (phylogenetic) and functional diversity, can help buffer the intensity of these invasions. Overall, the research highlights how human activity can supersede the influence of ecological processes when it comes to non-native tree invasions, particularly at early stages of invasion, but that native diversity may be an important tool to reducing the extent of invasions. “We found that globally, native biodiversity can limit the severity – or intensity – of non-native tree invasions,” said Dr. Camille Delavaux, lead author for this study. “This means that the extent of invasion can be mitigated by promoting greater native tree diversity.”

“This global understanding about the vulnerability of different regions to non-native trees will be critical for facilitating effective decision making to protect natural biodiversity,” said Prof. Dr. Thomas Crowther, a lead author of the study. “This global perspective would not have been possible without the amazing cooperation of scientists across the globe.”

Countries like the Netherlands, Singapore, Panama and China have particularly important ports in the context of this critical topic. Every single year, Dutch seaports handle over 550 million tons of goods: making seaports vitally important to the Dutch economy. Projects like Broekpolder and many other projects across the Netherlands play a critical role in restoring and protecting biodiversity, which in turn benefits the Dutch economy and ecosystems alike across Europe and the world.

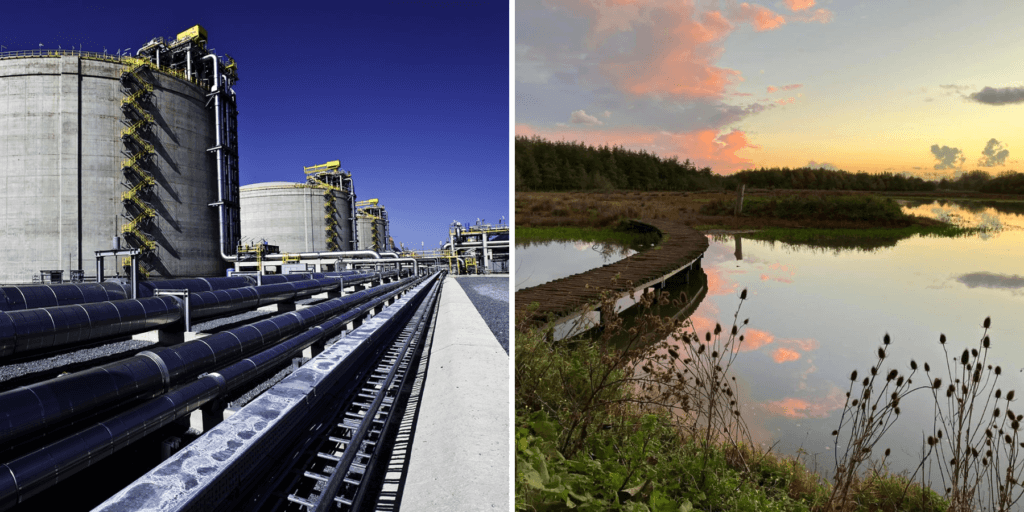

Storage tanks with heating pipes © Eric Bakker // Current scene from the formerly degraded Port of Rotterdam, which was filled with toxic sludge in the 1960s; now it’s home to unique biodiversity and is thriving due to the hard work of the local community!

Driving policy forward using science: the impact of invasive species on biodiversity loss around the world

These findings are particularly notable in the context of current global biodiversity conservation efforts. Reducing the establishment and spread of potentially-invasive non-native species is the focus of Target 6 of the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework. This study aims to support the upcoming Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) report, which is expected to highlight the substantial impact of invasive species on biodiversity loss globally.

There is a need for a better predictive understanding of non-native tree species invasions in close alignment with global biodiversity conservation goals and efforts. Because what do rabbits and the Dutch economy have in common? A critical need to support native biodiversity for the health of the entire ecosystem – and economy.