Leaves are not just leaves: what leaf types can tell us about our forests

Eight years ago, a global study from Yale University made the headlines. Researchers, led among others by lab founder Prof. Dr. Thomas Crowther, collected existing ground-sourced and satellite data, and counted that Earth is home to a staggering three trillion trees, which equals 422 trees per human being.

The resulting map revealed much about where tree density was highest or how many trees we have lost since the start of modern human civilization. But it did not really give insight into what kind of trees these three trillion trees are composed of. Eight years later, we set out to count the abundance of different tree types – only this time, we are looking at leaf data instead of tree density data. Now you may ask, why leaves?

The importance of leaves for forest ecosystems

There is a well-known simulation of the carbon cycle by NASA that visualises how CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere move throughout the year. In the winter months, high concentrations colour the map red, but as we move into summer, they slowly fade away – for one simple reason: the emergence of leaves on trees. Through processes like photosynthesis, transpiration, respiration, and litterfall, leaves are key agents not just in the carbon, but also the water and nutrient cycle of forest ecosystems worldwide.

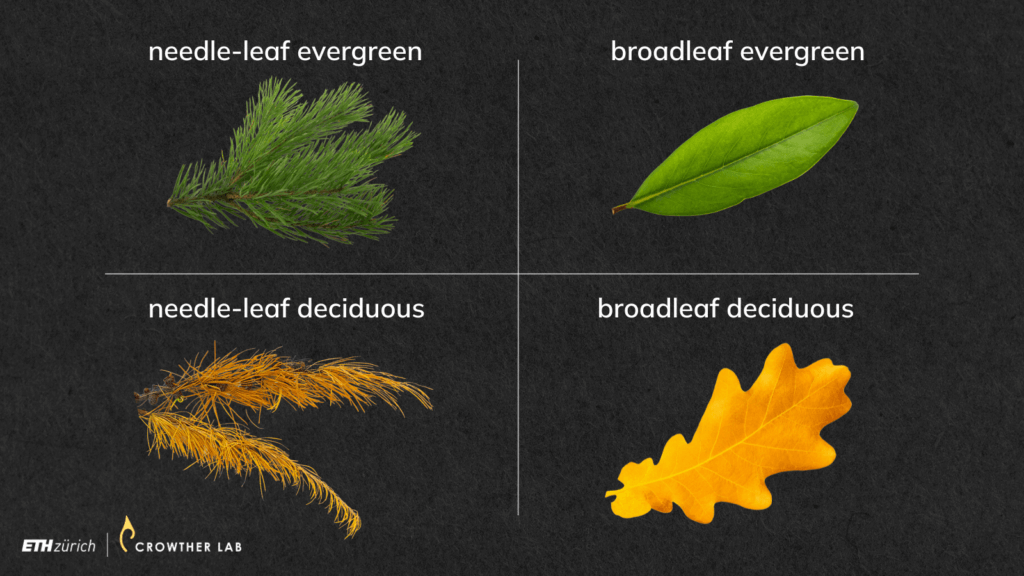

But leaves are not just leaves. They come in a wide variety of properties – like texture or colour – that reflect evolutionary adaptations to a plant’s needs and environment. Led by PhD student Haozhi Ma, our research focused on two leaf traits: leaf habit and form. Leaf habit refers to whether they are deciduous (shed by a plant during unfavourable seasons) or evergreen. Leaf form refers to the distinction between needles and broadleaves. In combination, these two traits result in four leaf types with which to count the world’s trees: needle-leaf deciduous and needle-leaf evergreen, and broadleaf deciduous and broadleaf evergreen.

The four leaf types in Ma et al. (2023)

Number vs. biomass: mapping the world’s leaf types

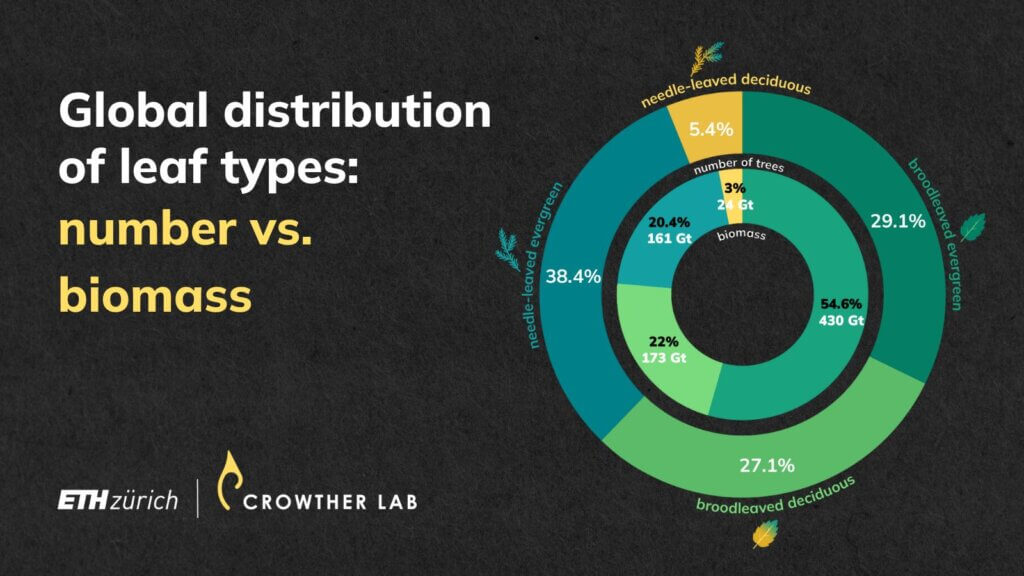

The analysis, the first to globally count and map leaf types, shows: at 38%, needle-leaf evergreen trees make up the highest number of trees around the world. In second and third place come broadleaf evergreen trees at 29% and broadleaf deciduous trees at 27% respectively. Last but not least, needle-leaf deciduous trees comprise at 5% the smallest number of trees on Earth. The abundance of needle-leaf evergreen trees aligns with the trillion trees study by detecting the highest tree densities in boreal and subarctic regions, which are home to needle-leaf evergreen trees.

The distribution of leaf type abundances, however, gets more interesting, when put in comparison with how much aboveground forest biomass is stored in each of the four leaf types. Research shows that broadleaf evergreen trees actually contribute the most biomass, making up 54% (335.7 Gt C) of the world’s aboveground forest biomass. So, while there are much more needle-leaf evergreen trees than there are broadleaf trees, needle-leaf evergreen trees in comparison only store 21% (136.4 Gt C) of the global aboveground forest biomass.

Leaf types and future forests

These findings come at a time when global forests are receiving a lot of attention. In recent years, much hope has been pinned on forests as allies in efforts to draw down human carbon emissions. Understanding how much carbon broadleaf evergreen trees are able to store as well as how comparatively few of them exist highlights that they are very much worth protecting. After all, forests face a variety of threats such as deforestation, excessive wildfires, biodiversity loss – especially in tropical regions where many broadleaf evergreen trees can be found.

Climate change will place additional stress on forests around the world. Assessing three different future emission scenarios, we find that up to one third of Earth’s forested areas are likely to experience climatic changes and stress by the end of the century. We just aren’t sure whether some regions can still be home to trees of the same leaf types as today.

To counter the risks that climate change brings, drastic emission cuts now will be necessary, as the conservation and restoration of forests alone are not silver bullets. That said, research like ours, can help to see the forests for the leaves – by both improving future modelling efforts of the global carbon cycle, and by guiding forest conservationists and managers to make informed decisions.