Ocean islands do not follow observed biodiversity patterns

One of the most basic patterns of biodiversity on Earth is that species diversity is highest near the equator, and declines toward the poles. New global biodiversity research, published in Nature, finds that oceanic islands break from this pattern, with islands in the tropics not much more diverse than those in higher latitudes. The loss of mutualistic interactions on low latitude islands may explain why.

Wind, water, or birds: this is how many plants make their way to oceanic islands. But mutualistic plants, reliant upon relationships with other organisms to establish also depend on the arrival of their partner. A new study finds that the overwhelming loss of mutualistic plants on islands disproves a familiar global pattern: that plant diversity always increases closer to the equator.

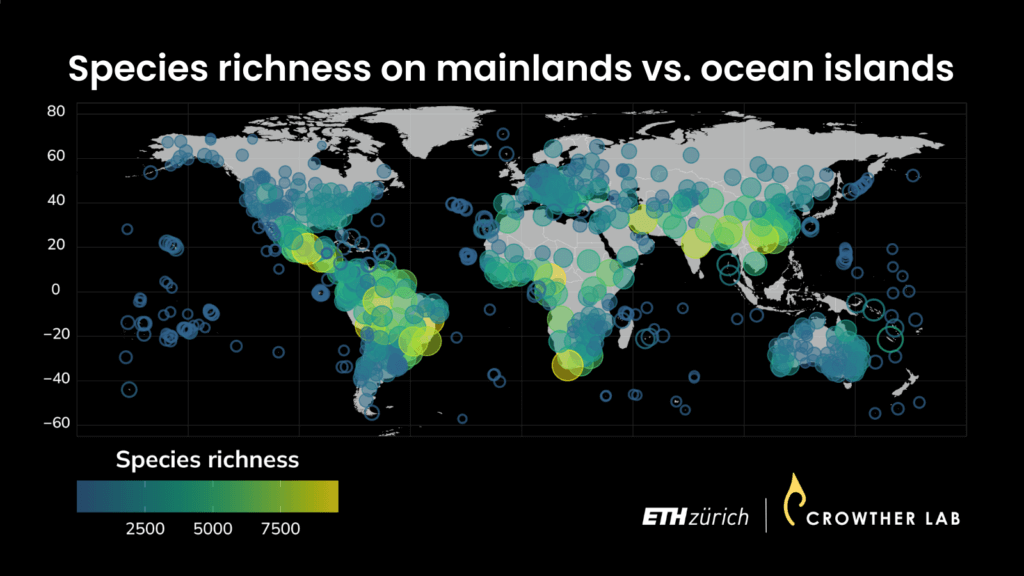

Biodiversity, particularly that of terrestrial plants, is known to be globally distributed along latitude, generating what is known as the latitudinal diversity gradient (LDG). In the lower latitudes near the equator, species richness is high, but declines at higher latitudes. That is, boreal forests are found to be generally less diverse than tropical forests. But is this always the case?

A new publication in Nature shows for the first time that this understanding of the LDG does not hold up for the flora of oceanic islands. Previous research on island biogeography mostly focused on physical drivers of species diversity, such as their smaller area or extreme isolation. In contrast, this study finds that the failure of species to arrive on islands relative to mainlands is governed by mutualistic interactions. The plants that rely on mutually beneficial relationships with pollinators, mycorrhizal fungi, or nitrogen-fixing bacteria for their survival are not as successful in colonising islands. Though their seeds may reach islands, it is not guaranteed that their mutualists will be present. Hence, fewer mutualistic plants are established on oceanic islands.

“Not only are mutualisms important for plant colonisation to oceanic islands, but they are more important than all other traditionally studied variables combined,” says Dr. Camille Delavaux, the lead author of the study.

Using data from 354 islands and 608 mainland regions, the scientists found that this filtering effect is especially strong in the tropics. The limited abundance of pollinators (e.g. bees) and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on these islands contribute 95% and nearly 85% respectively of unsuccessful colonising species among tropical oceanic islands. This means that mainland areas in the tropics may have 95% more plants reliant upon pollinators than an island at the same latitude.

“It is astonishing to think that tropical islands are not considerably more diverse than those in the higher latitudes. This important role of mutualisms completely transforms our fundamental understanding of how biodiversity is shaped,” said Prof. Dr. Thomas Crowther, professor of ecology at ETH Zurich.

However, the findings are no reason to believe that urgent introduction of more pollinators or soil fungi to oceanic islands are in order. Islands are simply less diverse than mainland areas, and we need to protect their native flora and fauna. Rather, the study raises awareness for how important mutualisms are for global biodiversity. They are key both to the understanding of lower island plant diversity and, vice versa, for the maintenance of high mainland plant diversity. This insight is not only valuable for future scientific research but also important for conservationists and restoration efforts on the ground.

Based at ETH Zurich, the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, Crowther Lab is an interdisciplinary group of researchers creating the scientific foundation for the protection and restoration of nature. The Nature publication “’Mutualisms weaken the latitudinal diversity gradient among oceanic islands’” will appear at this link once the embargo has lapsed: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-024-07110-y

For media enquiries:

Samantha Suarez-Maier, Communications Director

press@crowtherlab.com